The Philippine Scouts

Following the Treaty of Paris in 1898, the United States took precarious possession of the Philippine Islands in the far western Pacific Ocean, previously controlled for over 300 years by the Spanish. After a recommendation by Territorial Governor William Howard Taft, the 60th U.S. Congress passed Public Law 154 in 1908, which permitted “four Filipinos, one for each class, to receive instruction at the United States Military Academy at West Point… to be eligible only to commission in the Philippine Scouts.” Though the Philippine Scouts are now defunct, the law otherwise remains in effect.

A New Foreign Life

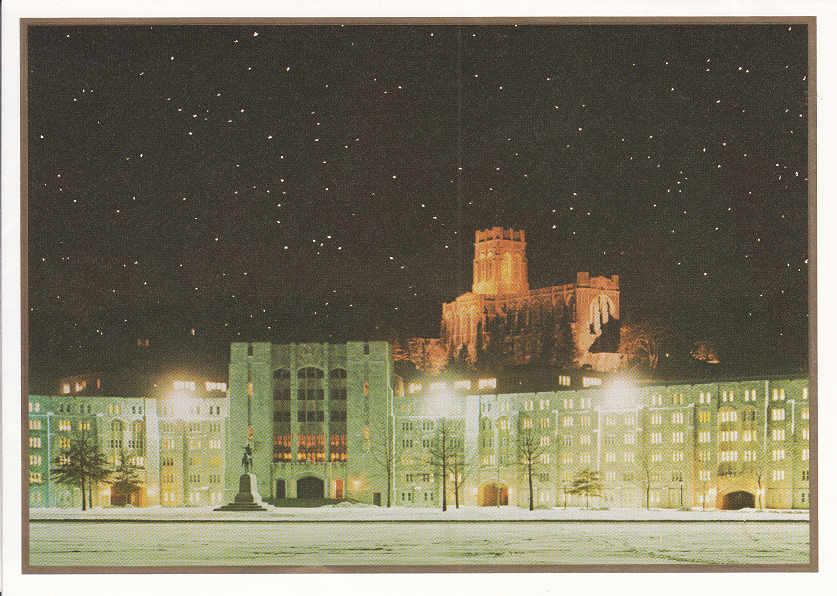

Santiago Garcia Guevara (1899-1996) was an ordinary lower-class Filipino, inspired to more by meeting one or more of the eight fellow Philippine nationals who now wore the uniform of an officer in the U.S. Army. One of nine honor students in his 1918 Manila High School graduating class, Santiago attended the University of the Philippines for one year. In 1919 he was awarded one of two Filipino appointments to the U.S. Military Academy (USMA) at West Point, New York. Accelerated war-time graduations had left only one Filipino enrolled at the Academy. In fact, when the armistice came in November 1918, only one class then remained at West Point. The appointment was a prestigious honor. He traveled across the Pacific with his new classmate Alejandro D. “Joe” Garcia (no relation), a three week journey on the U.S. Army Transport Sheridan with likely ports in Guam and Pearl Harbor, the first of what would be several trans-pacific journeys for Santiago. In his book The Regulars (©2004, Belknap Press) Historian Edward M. Coffman reported these transports only made the crossing four times a year. Hundreds of people would have been at the pier seeing people off, and welcoming new arrivals. This crossing began the adventure of a lifetime for Santiago, a starry-eyed nineteen year-old. After a stop-over in San Francisco, the young men took a multi-day journey by train to New York and their new, foreign life. 1919 marked the 50th anniversary of the U.S. transcontinental railroad, and was the apex of the railroad era. Traveling by train was an adventure in and of itself. As they watched the magnificent scenery pass, Santiago and Joe must have marveled at the size of America, contemplated their future, and anxiously anticipated what awaited at the end of the rail line.

Douglas MacArthur

In 1919 the time was right for a top to bottom rehabilitation of the Military Academy, and the Army felt 39 year-old Douglas MacArthur (USMA class of 1903) was the man for the job. MacArthur was a former Philippine Scout officer and the son of Civil War General and Medal of Honor recipient Arthur MacArthur. Douglas had gained a solid reputation in Europe, though in the words of Edward Coffman:

“With his crush cap and riding crop and the aura of being one of the top combat commanders [of the war], MacArthur’s presence must have been irritating to the oligarchy of permanent professors who composed the academic board… Nevertheless, he was able to get through a broader social science program, introduce[d] courses in modern technology… brought in civilian educators and consultants… attacked the hazing problem and gave cadet officers more responsibility. Then he liberalized discipline and systemized the honor code. It was a herculean task.” (pg 226)

Cadet Santiago G. Guevara ca. 1923

Santiago Guevara at West Point

The careers of Santiago and Douglas would be intertwined for the next 30 years. During his Academy years the cultural differences, cold winters, educational expectations, and the severe physical and psychological demands at West Point likely triggered loneliness and homesickness. Santiago’s ethnic identity, a source of both dignity and of discrimination, added to his stress, and racial politics and prejudice cast a continual shadow over his Army career.

Classes at West Point included math and engineering, law and languages, history and military drill and tactics. Most of Santiago’s professors were graduates, including future General of the Army Omar Bradley (class of 1915). There were no academic electives. Athletics offered opportunities to pursue individual interests and display skills in competitive sports. MacArthur believed that athletics was great preparation for military leadership and he inaugurated an intramural program and made participation mandatory.

Despite his tropical upbringing, in the 1923 Howitzer yearbook his classmates ribbed Santiago that “The beckoning call of the Philippine Seas never lured him away from the safer realm of dry land.” He was apparently neither an accomplished swimmer (“Guey was a charter member of the walri squad… who nearly drown[ed] his instructor”) nor a natural horseman (“Three times in one short hour he has been known to leave his horse and clasp the earth to his bosom until it permeated his hair, mouth, clothing – yes his whole being”). Unsurprisingly, Santiago decided the infantry might be his calling.

Classmate Harold D. Kehm later wrote that during their era the Academy underwent many

“academic changes aimed to reflect the lessons learned from WWI. In organization leadership and character training and conduct, the changes were extensive. It was in our day that the MacArthur and Danford1 concepts of discipline were evolved and applied.” The Cadets “were paraded for leading WWI Generals, for Queen Marie of Roumania, for princes of Belgium, Roumania, and England, and for dedication of the “Gold Tooth.”2 We summered at Ft. Dix and Ft. Wright. We played our part in the rise and fall of “The Bray”3 and the Cadet Band.”

Forty years later in a public speech, Santiago remembered “Beast Barracks,”4 the Honor system, furloughs and maneuvers, the 100th Night Show,5 and the Army-Navy football game.

In that same speech, Santiago also mentioned Summer Encampment. While at USMA, MacArthur had the Cadets train at Ft. Dix, New Jersey and then compelled the young men to march back to West Point with full packs, ”and so we set out, heavy laden and light hearted, a hundred thirty-five miles to do, and ten days to do it in.” This exhausting and protracted march foreshadowed another forced march well into Santiago’s career, that one heavy of heart and light of load, perhaps the defining event in his life and those of several other classmates.

Out of more than 450 cadets that entered the Academy in June of 1919, nearly half would wash out. Santiago and Joe persevered, finishing 219th and 208th respectively out of 261 June graduates. They were the ninth and tenth Filipino nationals to graduate from West Point. Upon graduation in 1923, Santiago was commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant and ordered to proceed to Fort William McKinley near Manila as an officer in the 57th Infantry Regiment of the Philippine Scouts.

1Robert M. Danford (USMA ’04) was USMA Commandant of Cadets from 1919 to 1923. Interestingly, he was also a contributor to the lyrics of the U.S. Army anthem, “The Caisson Song.”

²The “Gold Tooth” – L’Ecole Polytechnique Monument, still standing at West Point. Contemporary cadets are required to know and recite four supposed mistakes on the sculpture.

³The Bray – a short-lived student poetry publication.

4Beast Barracks – the traditional six-week introduction to military life, meant to break down individualism and teach obedience to authority.

5the 100th Night Show – a student-produced variety show performed 100 days before graduation.

Excerpted and adapted from West Point, Bataan, and Beyond: Santiago Guevara and the War in the Pacific © 2016 by Nick J. Guevara, Jr.

No Comments