The Philippine Military Academy

Lt.Col. Santiago G. Guevara, PMA Commandant of Cadets, 1941 (Source: The Sword of 1942 PMA Yearbook)

The attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii on December 7, 1941 is well documented. Coordinated Japanese attacks on the other side of the International Date Line, including Singapore, Guam and the Philippines, are less remembered. On that fateful day our grandfather Santiago Garcia Guevara, a Filipino West Point graduate, lived with his wife Carmen and their three children in Baguio, a mountain resort town about 150 miles north of Manila where Santiago was Commandant of Cadets at the Philippine Military Academy (PMA). Reports from Hawaii reached Manila by 2:30 a.m. Monday December 8, minutes after the Pearl Harbor attack had begun. Limited action was taken. Classes and drills were scheduled as usual at PMA, as were chapel services for the Feast of the Immaculate Conception, a Holy Day of Obligation.

Shortly after 8 a.m., instruction and worship was interrupted by explosions coming from Camp John Hay, an Army recreation area just a mile up the road from PMA and the site of the summer Presidential residence. As Santiago and the students rushed out to the parade ground and looked up, they saw two squadrons of Japanese Mitsubishi high-altitude bombers in “V” and diamond formations. As many as 150 bombs were dropped in a short period, with some falling on the grounds of the Academy, “shattering explosions that shook the ground.”

Over the next two days, continued bombing raids devastated remaining defenses, including Navy ships and facilities at Cavite, south of Manila. Much of what was left of the American and Philippine air force limped south, out of range of the Japanese airfields at Formosa (now Taiwan), along with most surviving U.S. and Philippine Navy ships, leaving Santiago and the rest of the soldiers on Luzon completely isolated and bereft of air and sea defenses.

Open City, Withdrawal to Bataan

Long-held war plans included declaring Manila an open city (the military practice of surrendering an area without a fight in hopes that the imminent conquerors will spare historic structures and not harm the civilian population). “It was tantamount to an open declaration of impotence,” grieved Santiago’s student Lt. Eliseo Rio in his memoirs, Rays of A Setting Sun. The troops were to then fight delaying tactics to allow the USAFFE troops in Northern Luzon the time to withdraw to the Bataan Peninsula. Once the Army held Bataan, it could deny the enemy the deep water harbor of Manila Bay and hunker down to await reinforcement by the U.S. Navy. Unfortunately, much of the Naval Pacific Fleet lay sunk or severely crippled at Pearl Harbor.

After organizing the cadets into the First Regular Division – Philippine Army (1D) , Santiago and his soldiers were ordered to meet a Japanese landing force, and when forced to pull back, the 1D retreated to the central Luzon Plain, where, trailed by thousands of refugees, they fought backwards in marches, convoys, and firefights toward Bataan.

The Philippine First Division on Bataan

“Bataan is shaped like a miniature Florida, with the southern end pointing toward Corregidor… Along its spine extinct jungle-clad volcanoes rise to nearly 5,000 feet. Rivers are treacherous. Cliffs are unscalable. Between huge mahogany trees, ipils, eucalyptus trees, and tortured banyans, almost impenetrable screens are formed by tropical vines, creepers, and bamboo. Beneath these lie sharp coral outcroppings, fibrous undergrowth, and alang-alang grass inhabited by serpents, including pythons. In the early months of the year, rain pours down almost steadily.” William Manchester, American Caesar: Douglas MacArthur 1880-1964

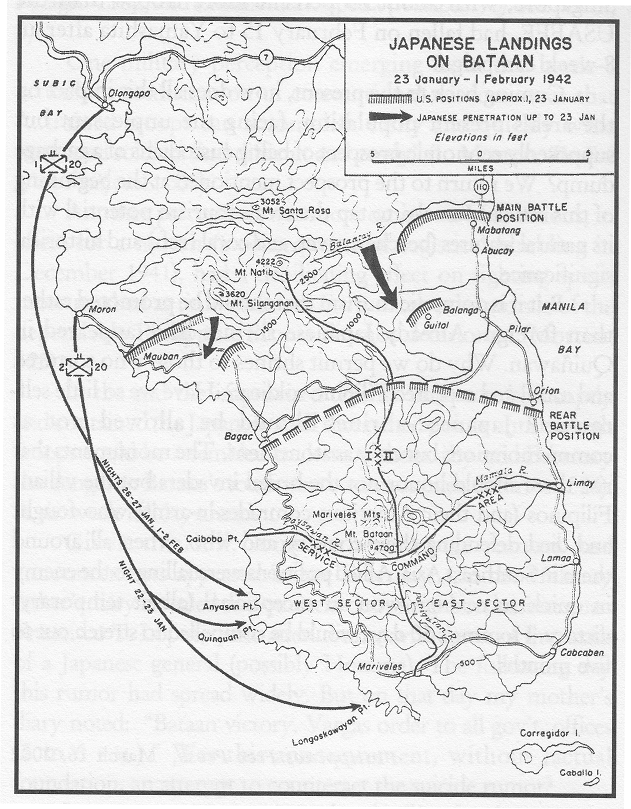

Map of early Bataan battle. “Quinuan Pt.” is the battle area also known as Agloloma Point. (Source: Occupation ’42 by Benito J. Legarda Jr. pg 42)

An estimated 80,000 Filipino and American troops dug defensive positions and prepared to defend the peninsula against the enemy and await relief. The First Regular Division was assigned to I Corps and asked to defend a nearly ten-mile wide sector from the village of Morong (also called Moron) on the South China Sea to the extinct volcano Mt. Natib, soaring 4,500 feet above sea level.

Agloloma Point

Santiago and elements of the 1D were asked to split off well to the south, and were credited with one of the first successful operations against the enemy on Bataan at Agloloma Point, for which he and the First Division received commendations from President Manuel Quezon and Gen. Jonathan Wainwright, the commander of forces on Bataan. Wainwright wrote in his memoirs that, “The first blows [on Bataan] did not come from the north, as was expected. [Instead the Japanese] landed at four points along the southwestern and southern extremity of the peninsula… At Agloloma Point the Japs hardly touched the beach.” Santiago’s commander Gen. Fidel Segundo explained, “In the morning a group of about 300 Japanese tried to make a landing in the beach. Our artillery saw it and let them have a taste of our shells. They ran away leaving about 150 dead and their guns.”

Surrounded

Shortly afterward, the 1D main line of resistance from Morong to Mt. Natib was infiltrated by a large enemy force and much of the division, including Gen. Segundo and Col. Guevara found themselves nearly surrounded by the enemy. After a tense two days nearly all were able to escape only by abandoning much of their large equipment and wading around rocky outcroppings to the safety of the rear lines, aided by a heroic covering force from other elements of the division.

The Battle of the Pockets

For weeks units from the 1D fought battles big and small. In addition to Morong and Agloloma Point, these included the Layac Line, the Porac-Guagua Line, the Abucay-Mauban Line, and the Battle of Trail 2. Their longest and most intense engagement was the victorious Battle of the Pockets, bordered to the east by the Tuol River. It began on January 26 and the enemy was engaged nearly twenty-four hours a day until February 17, including periods of bitter, hand-to-hand fighting. Japanese forces had broken through the latest line of resistance, the Bagac-Orion line, and were deeply entrenched behind the 1D in two separate “pockets” of troops, about 1000 Japanese soldiers in all. For a time, the enemy attacked on two fronts, from the pockets in the rear and from the Japanese main line of defense in the front. Because the 1D fought valiantly, the latter disengaged and abandoned their countrymen to their fates. An American officer gave the First Division the apt nickname, “the Meat-Grinder division.” Now-Capt. Rio related that:

“With the elimination of the “Big Pocket,” uncanny silence returned to our sector. I began to hear the native sounds of the jungle in the early evenings again. The most notable were the monotonous screeching of the cicadas and the deep-throated croakings of the toads and tree frogs. But the birds with their cacophony of sounds that engulfed us when we first came to Bataan might have been driven off by that infernal tumult, for they never returned for the rest of our stay. After more than a month of the continuously terrifying and shocking pandemonium of a fierce modern battle, the ensuing silence struck me as quite eerie, and it took a while for me to get used to it again. Sometimes in the depth of a pitch-dark night, I would awake to the deathly silence about me and sit up with a shiver and start thinking I was in a tomb buried alive.”

The 1D sent out regular patrols to feel out the enemy. A squad of eleven led by Lt. Restituto Joson, the “Cadet First Captain,” – the highest ranking cadet officer at PMA when the war broke out – was ambushed and killed during one such mission in February. Lt. Joson was one of eighteen members of the PMA class of ’42 who did not survive the war.

Abandoned, Sick, and Starving

In late December 1941, in response to the situation in the Philippines, U.S. Secretary of War Henry Stimson stated flatly, “There are times when men must die.” As they would soon come to understand, the Bataan defenders had been abandoned. During the three month siege, bitterness and defeat on Bataan came slowly and steadily. Put on starvation rations, historian William Breuer wrote they were fed, “—less than a cup of rice daily per man—they ate dog, cat, lizard, monkey, and iguana meat.” Horses and mules, including some from the PMA stables, became “cavalry steak.” After they were gone, scholar Richard Sassaman quoted one corporal, “We killed and ate snakes, cats, monkeys, and anything else that had meat on it.” Capt. Rio said that in addition to their “rice gruel,” the men tried to eat “leaves, flowers, roots, lizards, frogs, bugs, and worms.” The troops were bombed and strafed mercilessly, propagandized, and subjected to various diseases. 80% would contract malaria, 75% dysentery, and 35% beriberi. Other ailments included dengue, typhus, typhoid, hookworm, pellagra, and gangrene. 1D company commander Antonio Gonzalez described the desperate situation:

“The number of casualties kept mounting… There was no time, and no letup in the battle grounds, for the proper disposal of the dead. There was no time, and no means available to take care of the sick, the wounded, and the dying. In the immediate vicinity of my company in March hundreds of corpses were strewn all over the place, like so many “tinibans”1in a plantation. There were piles and piles of the dead from both sides along a shallow stream, the source of our drinking water. How can one now ever imagine the filth, the flies, the deadly mosquitoes, the incessant hunger and thirst, the ever-pressing dangers, the ugliness and gloom all around, the heavy stench of the dead?”

1tinibans – cut down bunches of bananas.

General Wainwright described Bataan as “a hopeless hell where everything was bad except the will to live, the memories of home, and the ever dimming hope that the great country we represented would somehow find a way to help us.” Sick, starving, and trying to avoid sinking into despair, their shared ordeal continued. In mid to late February the offensive slowed considerably as Japanese Commanding General Mosaharu Homma’s 14th Imperial Army was resupplied and reinforced.

The Via Crucis

By April 3, Good Friday, Carmen, the children, and other Catholics in Manila walked the Via Crucis. But the men of Bataan had already been through months of their own version of the Stations of the Cross: wallowing in their own filth; intense heat and humidity during the day and shivering cold by night; disease, exhaustion, and hunger; surrounded by suffering and death. Unknown to the men on Bataan, their personal road to Calvary still loomed. Santiago would have commemorated Holy Week, and would cling to his faith in God through these hellish times. He would not have been alone. It was on Bataan that Catholic chaplain William Cummings is credited with stating, “There are no atheists in foxholes.” Father Cummings, highly honored today by his Maryknoll order of missionaries and priests, later died on a prison ship enroute to mainland Japan.

Easter week, April 3-8, the reinforced Japanese Army began renewed artillery and strafing that spelled the end for the beleaguered troops. One private was quoted by Richard Sassaman:

“Thousands of rounds an hour (were) falling in an area not more than a mile in depth. We lost every gun, every truck, and every piece of equipment we had… At first it was every unit for itself. Later, it boiled down to every man for himself.”

Surrender

Finally and inevitably, the Filipino and American soldiers would “fall back to a place where there was no more back to fall back to.” On April 8, a series of earthquakes rocked Bataan, followed by a heavy rain the next morning. As the sun peeked out at high noon on April 9, 1942, 77 years to the day that Robert E. Lee surrendered 27,000 troops at Appomattox, Gen. Edward King met with Japanese Gen. Kameichiro Nagano and his translator Col. Motto Nakayama. As he laid down his pistol to officially surrender his 60,000 to 70,000 surviving men, only 15% of whom were in any reasonable condition to fight, King sought assurance that the soldiers would be treated humanely. “We are not barbarians,” replied Nakayama dismissively. What followed can only be described as one of the most barbaric episodes ever perpetrated on a modern army by another. It came to be known to history as the Bataan Death March.

Adapted from West Point, Bataan, and Beyond: Santiago Guevara and the War in the Philippines © 2016 by Nick J. Guevara, Jr.

No Comments