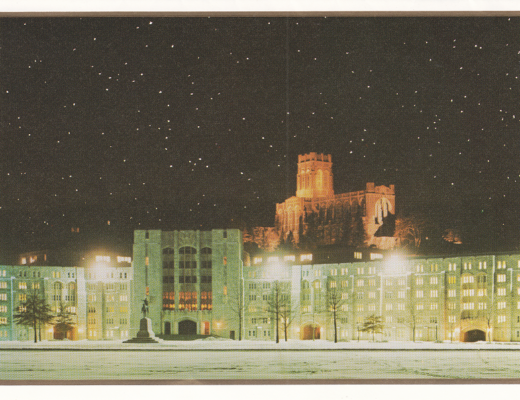

Military Heritage

William Morris Grayson (1915-1989) was our great-uncle, the youngest of seven children born to William Leon and Lillian Turner Grayson in Savannah, Georgia. Bill’s oldest brother Willie died of dysentery in 1899 just before reaching his second birthday. Their father, a colonel in the 1st Georgia Volunteer Regiment, was heavily involved in local politics and later worked closely with national political figures including Franklin Roosevelt. The Graysons were college educated and military minded. Eldest brother Spence (1900-1990) earned an appointment to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, but withdrew to pursue a successful career in the law and politics while brother Leon (1906-1993, our much-beloved grandfather) served as a stateside Coast Artillery Corps officer during World War II. Each of Bill’s sisters married career military officers; Lynne (1893-1961) wed future Coast Guard Commander Leo Mueller, Dorothye (1903-1961) was the wife of Naval Academy grad and future Admiral Sam Comly, himself the son of a Navy Admiral, and Edith (1912-1968) married future Navy Captain George Parsons. Like the youngest in many families, Bill probably did not excel with schoolwork. As a teen he was sent to boarding school in Annapolis, Maryland – likely through the influence of the Comlys – perhaps with the idea of earning an appointment to the Naval Academy himself.

University of Georgia

Bill instead eventually enrolled at the University of Georgia (UGA) in 1935, the Alma Mater of his brothers and sisters. He was involved in the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps, the Chi-Phi fraternity, and, though not an especially big man at 5’10” and 195 lbs., also played guard on the football team. Bill did not graduate (he listed “two years college” on a later document) but he thought enough of UGA to endow a scholarship upon his death through at least 2006.

Isle of Hope

Bill’s mother Lillie died in May 1936, and by the end of the following year he had left school and returned to the family home on Isle of Hope, taking up employment as a machine operator at Union Bag, whose Savannah plant was then said to be the largest paper mill in the world. Isle of Hope was and is a beautiful spot, situated at the end of a now defunct electric trolley line seven miles southeast of the Savannah Historic District. The Grayson home on Bluff Drive boasted a dock which extended into the tidal Skidaway River. As a personal aside, on a 1990s trip my wife was taking photos of the dock when I cautioned her to be a bit more discrete, pointing out the current homeowner working on his boat. “It was our house first!” she replied somewhat indignantly. The Grayson family sold the home in 1944. Though he would have objected, Bill was to have no say in the matter.

Army Air Corps

Bill enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Corps in October 1940. He had just turned 25. He went to basic training in Missouri, then specialty and flight training in California and New Mexico. While Bill was thus across the country, his father Colonel Grayson died at Isle of Hope of pneumonia, said to have begun during the bitter cold of President Roosevelt’s third inauguration, though family letters cast doubt as to whether he was well enough to have attended.

Flight Crew, Tower Duty

“I trained as a waist gunner on a B-17D,” Bill remembered. By the autumn of 1941, he was assigned to Clark Air Base on Luzon Island in the Philippines, 60 or so miles northwest of Manila. His last mission was a 15-bomber sortie over Japanese-held Formosa (modern-day Taiwan) on December 8, 1941. They observed multiple Japanese aircraft on the ground. “We had orders from [Gen. Douglas] MacArthur not to drop any bombs, so we didn’t,” he remembered with some bitterness. Within an hour of returning to Clark the tables were turned. “They hit us at 1:15 p.m. They were bombing and strafing. Afterward we had only 10 planes left out of 31.” Bill volunteered for tower duty, giving alerts for the numerous raids that followed over the next three weeks.1

Bataan – A Letter Home

All allied troops on Luzon were ordered to withdraw to the Bataan peninsula in late December, and there they fought the invading Japanese Army and underwent privation and starvation for more than three months. While under siege, Bill wrote a letter home dated February 14, 1942. His influential brother Spence, then a Georgia state senator, typed out copies for the family. It read in part:

I am O.K…. I wish I could tell you where I am and what I am doing. So far though I have been plenty damned lucky. I have lost everything I own, jewelry, clothes, etc. but I am not doing any too much worrying about that. I really have a lot to tell you all. I sure will be glad when this is all over and I can come back home…. This war really does open my eyes to a lot of things. It is not what it is cracked up to be though and I am going to be as careful as I can be. You never do realize how much you want to get back and how much you really do care!!

The Bataan garrison, under the field command of Gen. Edward King of Brunswick, GA, near Bill’s hometown of Savannah, ultimately surrendered on April 9, 1942. In what became known as the Bataan Death March, Bill remembered the ensuing multi-day trek of 65 miles. “We had no food for [the first] three days. If you lagged, you got shot or got a bayonet through you.”1 It was just the beginning of their ordeal.

Nightmare Existence

Bill described his subsequent years of what he called starvation and slave labor in prison camps on Luzon and Mindanao in the Philippines and, after a harrowing 90-day trip aboard a hell ship in which more than one-third of the captives died, mainland Japan. “When we started the trip to Japan, there was just enough room [in the ship’s hold] to stand back to back,” he remembered in a 1970 interview which stated he still visualized his dead comrades being weighted down and thrown overboard. “But when we got there we had enough room to lie down.”2

“We worked in the rice fields and on the roads and all we got to eat was three bowls of rice a day. There was no meat…. The only thing that got me back was that I never gave up hope. If you gave up hope… you were as good as dead.”2 A 1983 newspaper article began, “It’s been 38 years since William Grayson’s nightmare existence as a prisoner of war ended. But the bad dreams still continue. …“You never forget,” he said. “Three and a half years is a long time out of your life.”1

“I regret to inform you…”

If the Bataan letter did indeed reach Spence before the surrender, Bill’s siblings were aware that their baby brother was on Bataan and “O.K.” in early 1942. They may also have received news that he initially survived the April 1942 Death March. If so, it was the last they would hear of Bill for 14 agonizing months. Despite Spence’s political connections and repeated inquiries, no news was forthcoming. “I regret to inform you,” an April 1943 letter from the U.S. Adjutant General reads, “that the [missing in action] status of Private Grayson remains unchanged. The War Department is receiving partial lists of prisoners of war through the International Red Cross but to date the name of this soldier has not been found on any of the lists.”

The Telegram

Too many families received telegrams during the war, a great number of which began with the same, “I regret to inform you” of the April 1943 letter. The type that followed often removed any hope at all that their loved one was still alive. The Graysons still had hope, though the not knowing was in some ways nearly as awful as the confirmation of death. Finally, two months after the “We regret to inform you” letter, a telegram arrived at Spence’s Savannah office. Knowing what these telegrams often contained, how his heart must have sunk and his hands trembled as he opened the envelope and unfolded the communication.

Jubilance! And yet some pause at that awful phrase “prisoner of war.” The U.S. government had hidden from the general public what they had learned of the barbaric treatment of POW’s during the Death March and beyond, but still… Postcards arrived from Bill assuring he was indeed alive. Letters flew back and forth, some received, others never seen. Bill was barely one-third through his “nightmare existence,” but he was alive, and the siblings were spared the details of just how dismal that life was and would continue to be, should he indeed even survive.

Release and Return

Survive he did, though Bill, who weighed 195 lbs. at the outset, was a mere 85 lbs. upon liberation in August 1945. After release, he was hospitalized in Washington state for a time, where the letters continued, supplemented by phone calls. On the day Bill flew into Savannah’s Hunter Army Air Field, the city held a parade to honor their returned POW’s Gen. King and Cpl. Grayson. (Author note: just noticing Gen. King’s middle name “Postell,” the maiden name of Spence Grayson’s wife Margaret. A quick ancestry search reveals the great-grandfathers of Gen. King (Rev. Edward Perry Postell) and Margaret (John Dupre Postell) were brothers, making the General and Margaret Grayson third cousins. Small world. Surely they knew this, at least by the time of the parade?)

After the Parade

Bill returned to Union Bag, working in the forestry division then in sales, where he made his career. He married a girl from Massachusetts in early 1946, three months after his parade, so he must have known her before the war. Or perhaps not? In either event, the marriage did not last. Union Bag later merged with another family-owned paper business, Camp Manufacturing, to form the Union-Camp Corporation. He moved to New Jersey for his work, and married Mary Rose Stumpf in New York City in 1951. Bill never had children, and suffered the rest of his life with the after-effects of the abuse, malnutrition, and disease he endured during his captivity. It is believed he was sterile, possibly from his traumatic experiences. All the Graysons struggled with fertility issues, however.

Free Spirit

Bill and Mary purchased a summer cottage at Cape May Point on the Jersey shore, where he hosted friends and family for many years. “Aunt Mary was a sweetheart,” remembered their nephew Jim “Monroe” Parsons.3 Bill was very happy and outgoing but had periods of quiet too. “Nothing seemed to bother him. I guess after what he went through, why would it? My mother [Edith] called him ‘Ferdinand the Bull’ after the children’s book character that would rather lay in the clover than fight.” When his fellow POW friend Blair Robinette came to visit, Monroe reported the two would sit at the end of the porch for hours and quietly discuss their shared experiences. Not to say that he didn’t speak about it to others, as he and Mary were very involved in the leadership of the American Defenders of Bataan and Corregidor, in the publication of their newsletter “The Quan,” and traveled for survivor reunions every year. Bill and Mary loved their dogs, and upon their deaths, they made provisions to have the dogs buried with them at the Grayson family plot in Savannah. Bill and Mary seemed to be remarkable people. If I ever met them, I don’t remember it. And that is my loss.

1 Atlantic City (NJ) Press Thursday, Aug 4, 1983. The Survivors by Marjorie Donchey. Newspaper clipping in family possession.

2 Dover (NJ) Daily Advance (unknown date – possibly March 14 or 15, probably 1970). ‘Death March’ Recalled by Robert Rastelli. Newspaper clipping in family possession.

3 Many thanks to cousin Monroe Parsons for saving the documents pertaining to Uncle Bill and Aunt Mary, and his descriptions and stories of the couple. Monroe is the glue that continues to connect the Grayson descendants.

1 Comment

T

June 18, 2020 at 12:14 pmfantastic! fascinating! wow it could have been so much worse for Lolo…